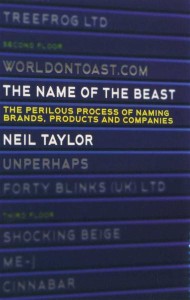

I’ve just finished reading a great book with an even greater title. The Name of the Beast by professional ‘namer’ Neil Taylor, is a guide to the ‘Perilous process of naming, brands, products and companies’.

I’ve just finished reading a great book with an even greater title. The Name of the Beast by professional ‘namer’ Neil Taylor, is a guide to the ‘Perilous process of naming, brands, products and companies’.

You can tell Neil is slightly scarred from his years as a senior naming consultant at Interbrand where he discovered (much like for graphic designers), everyone is an expert. And some are very cynical about the role of professional namers such as Neil.

According to Andrew Mueller in Guardian newspaper;

“There are people, enviable yet contemptible, who make good livings inventing names for companies.

…

In fact, if you’re a CEO about to shovel a five-figure fee at some twit called Nathan to come up with a name like Twerq or Zamp Plus or X-Zite!, get in touch – for half the money, I’ll do you something at least as good, and certainly no more foolish.”

And people often have strong emotional bonds to brands they have grown up with, and are now being ‘messed about with’. Neil give a classic example of name failure, when Royal Mail changed to Consignia in 2000. He prints three pages of hostile comments from the time, which culminated in an embarrassing ‘volt-face’ just 15 months later.

For me, the most useful part of the book is chapter 3 where he covers the different approaches to naming.

Descriptive names

By using the Ronseal approach, ‘they do exactly what they say on the tin’, see the history of the famous phrase. Obvious examples would be pretty much anything that starts with British (think Airways, Gas, Petroleum, Telecom etc). Sadly these names are often too good to be true, and cause problems when you go international, or change what you do over time.

By using the Ronseal approach, ‘they do exactly what they say on the tin’, see the history of the famous phrase. Obvious examples would be pretty much anything that starts with British (think Airways, Gas, Petroleum, Telecom etc). Sadly these names are often too good to be true, and cause problems when you go international, or change what you do over time.

Neil uses one of my favourite examples, The Carphone Warehouse. This name accurately described the brick sized phones sold in warehouse outlets when they were starting out. But today they sell sleek smartphones is smart high-street shops. I wonder if the chairman Charles Dunstone called a meeting one day to come up with a new name. But someone pointed out they had left it too late, and anyway the business was doing just fine with the original name. The positive brand values had been absorbed into the name, and risked being thrown away with a new name.

So although descriptive names save you having to explain what the company does, they have almost all already been taken, and even if not, can risk being too descriptive to allow you to register a trademark. For instance, Compare the Market and We Buy Any Car have been refused a trademark, but Compare the Meerkat and Webuyanycar.com were allowed.

So although descriptive names save you having to explain what the company does, they have almost all already been taken, and even if not, can risk being too descriptive to allow you to register a trademark. For instance, Compare the Market and We Buy Any Car have been refused a trademark, but Compare the Meerkat and Webuyanycar.com were allowed.

Image-based names

Moving on from literally descriptive names, image-based names work by association using metaphors. Neil gives the examples of Visa (the shopping equivalent of a passport) and Viagra (think life and Niagra). If successful this approach can give a brand a personality which can appeal to customers.

Abstract names

Some of the most powerful brands on the planet use abstract and in some cases, made up words. Apple is currently the most profitable business in history. George Eastman used Kodak because he thought k’s were cool, so why not have one at the beginning and end of his brand name? Citroen did something similar until relatively recently when they ‘owned’ the letter X. Starting out with CX, BX and XM and then moving onto more creative names such as Xsara and Xantia.

The best thing about a made up name is that it can’t already be registered as a trademark to someone else, although you do still have to be careful it isn’t similar to a word that is in use.

Names of provenance

These are abstract names, but derive from a place or person. In fact, nearly half of the world’s top 100 brands use family names. Examples would be McDonald’s, Ford, Cadbury, Kellogg’s and Dyson.

Names that break the rules

After spending many pages explaining the options for naming and going into detail about how to brain-storm for names, Neil give some examples of names that break the rules.

After spending many pages explaining the options for naming and going into detail about how to brain-storm for names, Neil give some examples of names that break the rules.

For example, I can’t believe it’s not butter, is about as far away from a short and simple brand name as you can get, even though it does sort of explain what the product is. He uses the example of U2 who have a ‘rubbish’ name but global success, whereas Half Man – Half Biscuit have brilliant one, but are long forgotten except by a few faithful fans. Or how about Smeg fridges? Surely no one would by a brand whose name is associated with “a substance that collects inside male genitalia”. But thanks to their bright colours and trendy retro design they have become very popular indeed.

I am glad to see that Neil spends a bit of time talking about trade marks, even if it is in a rather short chapter titled The long arm of the law. He points out how trade marks trump company or domain names, which means they need to be checked first. The famous cases of Apple Corps vs Apple Computer is covered, and Budweiser US vs Budweiser Czech lager beers.

He explains how a name can exist in different classes of business activity using Polo as an example – a VW car, a mint with a hole, and expensive clothing. As long as the consumer is not confused about what and who they are buying from, there is no problem.

Neil is definitely not a fan of trade mark lawyers, but does admit they can help you work out the risk of choosing a particular name. It all comes down to predicting how the owners of similar names with react. How likely are they to send you a ‘cease and desist’ letter from their lawyers?

So you don’t have to like a name, or understand what it means for it to be successful. As long as it is legal, available and memorable you should be ok. If Cillit Bang can become a household name, surely anything goes.

So you don’t have to like a name, or understand what it means for it to be successful. As long as it is legal, available and memorable you should be ok. If Cillit Bang can become a household name, surely anything goes.

There are so many great names out there to be discovered.

Today a customer mentioned Pixiwoo http://www.pixiwoo.com/ who are two sisters, make-up artists, bloggers, vloggers, columnists, who do makeup on youtube and run a free digital makeup magazine http://www.two-magazine.com

The Pixiwoo trademark is at https://www.ipo.gov.uk/tmcase/Results/1/UK00003018025