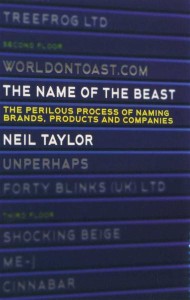

I just love business names. And I seem to come across new ones every day at work. Almost all the start-ups I meet want to have the perfect one to describe their business activity. But this is often impossible due to the UKIPO’s rules, and even when allowed can be a mistake.

For instance Carphone Warehouse chose a name that accurately described their business when it started in 1989. They were on the cutting edge of the new mobile-phone technology, and sold those marvels of miniaturisation known as car phones, through their first store located in – you guessed it – a warehouse.

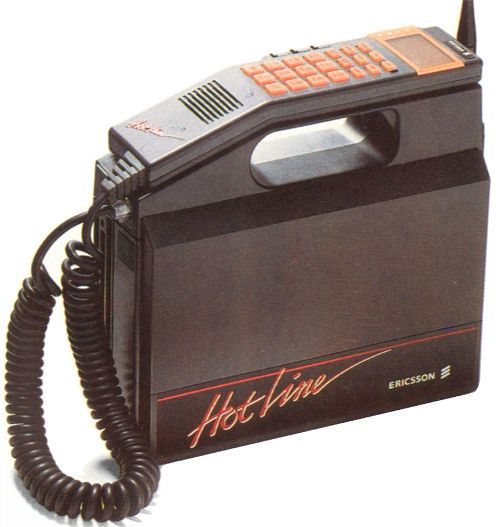

The first Carphone Warehouse and an example of an early mobile phone

It wasn’t long before the company expanded into the high-street, and their products shrank to the pocket-sized phones of today. So their wonderfully accurate name became doubly redundant. But by then they were a household name and were stuck with it. They did however learn from this mistake and use the brand PhoneHouse in the rest of Europe.

So that was an example of a good name which went bad thanks to the market moving. But some brands who started out with really bad names still managed to have great success. I covered Smeg in my blog post How to name your brand and get it trademarked. So I won’t dwell on the uncomfortable associations for that word again. But they certainly haven’t held their business back.

Or how about Soylent, the company that claims to have created the future of food?

It certainly look futuristic enough, although maybe not a appealing as my favourite Amelia Rope chocolate. But what I don’t understand is why the founder Rob Rhinehart chose to name the food after the 1973 science fiction film Soylent Green. It starred Charlton Heston and was set in a dystopian future, where the only food left on our dying planet is a green wafer known as Soylent Green. The movie ends with the shocking discovery that this staple is manufactured from humans. Or, as the final scene whispers; “Soylent Green is People!”

Here again, what on paper would appear to be a truly awful name, has not stopped the company from becoming very successful.

Closer to home we have the very popular fashion brands Fat-Face and Sweaty Betty. More proof that a horrible name is no barrier to success.

Closer to home we have the very popular fashion brands Fat-Face and Sweaty Betty. More proof that a horrible name is no barrier to success.

Possibly the worst idea of all is to be nameless, but search Google for Nameless and you will find plenty of brands. Such as a ‘tech’ fashion brand in Moscow, and a digital marketing company in Bristol.

Returning to the world of science fiction we have SkyNet. An express courier network founded in 1972 that has grown to be the world’s largest. They can deliver “from a postcard to grand piano, to or from almost every country on the planet”.

But type ‘skynet’ into Google image search you will

But type ‘skynet’ into Google image search you will see this logo closely followed by the infamous terminator robot:

see this logo closely followed by the infamous terminator robot:

Let’s get back to some great names. On my cycle to work I have recently spotted vans sporting the memorable Magicman registered trade mark. Who wouldn’t want to employ the services of a “technician trained to deliver incredible repairs to wood, stone, marble,uPVC, veneers, laminates, granite, ceramic tiles, stainless steel and even glass. We rectify chips, dents, scratches, burns, holes and so much more on site, nationwide”?

I think we should end with a couple of brands that follow the Ronseal approach to naming. In other words, they do what they say on the tin.

First we have Sticks Like Sh*t. For those in the building trade the name effectively, if rather bluntly, explains what the product does.

First we have Sticks Like Sh*t. For those in the building trade the name effectively, if rather bluntly, explains what the product does.

Although I was intrigued to discover that on the manufacturers website the name has been bowlerised to Sticks Like Adhesive.

Perhaps they don’t want to upset the more sensitive home DIY brigade? The owners Bostik have registered the name with the UK IPO, so don’t think about copying it!

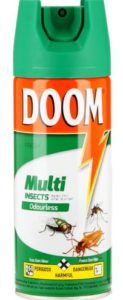

Finally we have my favourite brand name of all time. Strong, simple and memorable, with a clear

Finally we have my favourite brand name of all time. Strong, simple and memorable, with a clear indication of its purpose. I first came across Doom on safari in Kenya in 1982. I still remember clearly the moment a can was produced and liberally sprayed onto a very large and scary insect which happened to be walking across the entrance hall of our lodge. It didn’t take long for the creature to cease to be a threat.

indication of its purpose. I first came across Doom on safari in Kenya in 1982. I still remember clearly the moment a can was produced and liberally sprayed onto a very large and scary insect which happened to be walking across the entrance hall of our lodge. It didn’t take long for the creature to cease to be a threat.

Sadly the brand is now more closely associated with the computer game of the same name. Although I was glad to find a less dramatically packaged version still for sale in South Africa.